Tim talks ticks!

Ticks are widespread in the UK. The most common ones found on dogs and people are sheep and deer ticks but there are many others with different hosts. Recently, exotic ticks have become established in southern England, and these could spread in the future.

Ticks can be caught almost anywhere outdoors, but wild areas with heavy vegetation give the greatest risk. They prefer warm and damp conditions but are active at temperatures >5oC so they can be a year-round problem in much of the UK.

The lifecycle is similar for most ticks. Fully fed adults lay eggs in plant cover. These hatch into tiny larvae that seek a host for a blood meal – the initial hosts are usually small rodents. The fed larvae then detach and moult into nymphs. These again seek a host, which can include larger animals. The fed nymphs detach and moult into adults. The adults usually seek larger hosts, such as sheep, deer, dogs and people. The fully fed ticks then detach to lay their eggs and start the life cycle again.

Ticks can’t directly pass from host to host (e.g. between dogs or between dogs or humans). However, an infested animal can be responsible for spreading ticks into a previously tick-free environment. The ticks found in the UK are outdoor and are unlikely to complete their life cycle indoors (although this happens elsewhere in the world).

Ticks can transmit a variety of diseases to people and dogs. Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi) is most familiar but there are others that can cause anaemia and other systemic (involving internal organs) conditions. Exotic ticks are a concern as they can transmit a wider range of diseases.

The aim of tick prevention is to reduce the risk of disease transmission. In the context of Wag & Company, we also want to minimise the risk of moving ticks to the places we visit (e.g. gardens in nursing homes). Lastly, dogs that travel abroad can bring exotic ticks into the UK (this is probably how they became established in southern England).

There are a range of safe and effective products that can be used to repel and/or kill ticks and you can discuss which would be most appropriate for your dog with your vet – for example, they will need to consider whether the product is affected by swimming or bathing, other parasite control (e.g. fleas and worms), and if there are cats in the house.

No anti-tick product gives 100% protection, and some take several hours to be effective. This means that a tick can still attach before it is killed. Most disease transmission takes 12 hours or more, but it may happen much more quickly. It is therefore also important to check and remove ticks after being outside in likely tick habitats. The adult tick is about 2-3mm long, dark and flattened with eight legs and a hard protective shell. The softer abdomen expands after feeding to produce the familiar grey 7-10mm bean-shape. An illuminated hand lens can be helpful to magnify anything suspiciously ‘tick-shaped’ – the head, mouthparts and legs should be obvious. Non-attached moving ticks can be lifted off and crushed (which is surprisingly hard – fingernails are best). Tick removers are best for attached ticks – pulling the body can sometimes leave the head and mouthparts in the skin.

You should take you dog to your vet if you notice any swelling and inflammation at the site where a tick was removed. Veterinary advice should also be sought if you see any fever, malaise or other illness after tick exposure. Don’t wait for the classic red target lesion – this is specific for Lyme disease in people and is rare in dogs.

In conclusion, ticks are common and there is a risk of disease transmission. Effective anti-tick products can be used to reduce the risk. However, these shouldn’t be relied on and routine ‘check-and-remove’ is a good idea.

Dr Tim Nuttall

Wag & Company Veterinary Advisor

Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, University of Edinburgh.

Figure notes

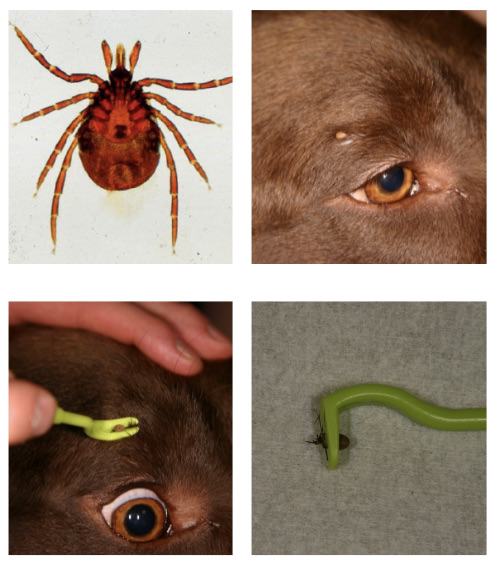

Figure 1 – an unfed adult Ixodes ricinus (the castor bean or deer tick) magnified 100x.

Figure 2 – a partly fed and engorged Ixodes species tick above the eye in a Labrador; this tick was found in later October in Scotland.

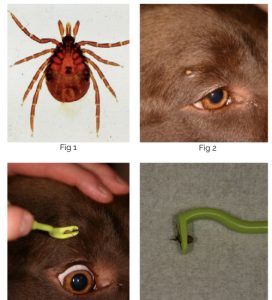

Figure 3 – using a tick remover; the hooked part with the slit is slid between the tick and the skin, and then it is twisted and lifted to remove the tick.

Figure 4 – the tick has been successfully removed; you can see the head, mouthparts and legs still attached to the body.